School of Rock (2003) is one of my favorite music movies, and was on my previously published list of 30 Music Movies You Need to See Right Now. It contains a staggering amount of references to well-known rock bands through the decades. But it also contains a surprising amount of small nods to lesser known artists—the kind you would only catch if you already loved those bands. So I did my best to catalogue what we have going on in the movie. Most of the references have some pretty interesting explanations, and the stickers that show up throughout the film span now only the decades, but numerous genres as well.

As it’s called the School of Rock, I only put time into doing my best to catalogue the rock artists and references, though during the “backboard scene,” labels like “R&B,” “Blues,” and “Hip-Hop” are clearly visible. I highly recommend checking out some (all) of these artists. I might be slightly obsessive, but I just like to think of myself as a music addict ;D I wanted to include as many pictures as I could, but since there are so many, I had to choose just a few. I left out album covers since those are easily recognizable, but grabbed a few screenshots of the awesome blackboard tree and a bunch of the stickers. Enjoy!

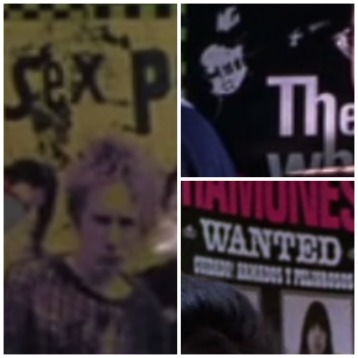

Posters:

- The Who – (in Dewey’s room)

- Ramones – (in Dewey’s room)

- The Walkmen – (in Dewey’s room)

- Sex Pistols – (in Dewey’s room)

- The Clash – (in Dewey’s room)

Stickers:

Stickers from Dewey’s room and public telephone; clockwise: (First panel) AC/DC, Lunachicks, Nine Inch Nails, Beastie Boys, White Zombie, Voivod, Red Hot Cili Peppers, L.A. Guns; (Second panel) Ratt, Fugazi, Cannibal Corpse, The Chemical Brothers; (Third panel) Godflesh, M.O.D.

- Black Sabbath – (in Dewey’s room)

- Nine Inch Nails (NIN) – (in Dewey’s room)

- Fugazi – (in Dewey’s room)

- AC/DC – (in Dewey’s room)

- Butthole Surfers – (in Dewey’s room)

- Ozzy Osbourne – (in Dewey’s room; on van outside audition)

- M.O.D. – (on public telephone)

- Godflesh – (on public telephone)

- The Strokes – (on the inside of Dewey’s van)

- Metallica – (logo on the inside of Dewey’s van)

- The Clash – (in Dewey’s room)

- Iron Maiden – (on the inside of Dewey’s van)

- Ministry – (on the inside of Dewey’s van)

- The Beatles – (on the inside of Dewey’s van)

- Joy Division – (on the inside of Dewey’s van)

- The Haunted – (in Dewey’s apartment)

- Stevie Ray Vaughan – (in Dewey’s room)

- Megadeth – (in Dewey’s room)

- Cannibal Corpse – (in Dewey’s room)

- Voivod – (in Dewey’s room)

- Beastie Boys – (in Dewey’s room)

- L.A. Guns – (in Dewey’s room)

- Red Hot Chili Peppers – (in Dewey’s room)

- Radiohead – (in Dewey’s room)

- The Chemical Brothers – (in Dewey’s room)

- Ratt – (in Dewey’s room)

- NOFX – (in Dewey’s room)

- Save Ferris – (in Dewey’s room)

- White Zombie – (in Dewey’s room)

- Lunachicks – (in Dewey’s room)

Albums:

- Led Zeppelin by Led Zeppelin

- Fragile by Yes

- Blondie by Blondie

- 2112 by Rush

- Axis: Bold As Love by The Jimi Hendrix Experience

- The Dark Side of the Moon by Pink Floyd

References:

- Jimi Hendrix – (when Dewey is trying to sell his guitar)

- Led Zeppelin – (when Dewey references bands that rock!)

- Jimmy Page (Led Zeppelin – guitarist)

- Robert Plant (Led Zeppelin – vocalist)

- Black Sabbath – (when Dewey references bands that rock!)

- AC/DC – (when Dewey references bands that rock!)

- Motörhead – (when Dewey references bands that rock!)

- Spice Girls – (Dewey refers to Katie as “Posh Spice” when assigning band positions)

- Blondie – (Dewey refers to blonde girl Marta as Blondie when assigning band positions)

- Neil Peart (Rush – drummer) – (Dewey refers to Peart when handing Freddie the album 2112)

- The White Stripes/Meg White – (Freddie refers to White when discussing “great chick drummers”)

- Glam rock/metal – (Billy refers to glam fashion when making the band’s costumes)

- Kurt Cobain (Nirvana – vocalist/guitarist) – (Dewey calls Zack Kurt Cobain when asking to hear the song he wrote)

- “For Those About to Rock (We Salute You)” by AC/DC – (lyrics recited by Dewey in his speech to class the night before the Battle of the Bands performance

- AC/DC – (No Vacancy bassist’s shirt during Battle of the Bands)

- Angus Young (AC/DC – lead guitarist) – (Dewey’s schoolboy uniform during the final Battle of the Bands performance is a direct reference to the schoolboy uniform Young is famous for wearing onstage; his burgundy Gibson SG model guitar is also the same model as Young plays)

- Sex Pistols – (referenced by Freddie when he notes “Sex Pistols never won anything” after the Battle of the Bands show)

- Ramones – (Zack wears a Ramones shirt during the credits scene)

- Green Day – (Freddie wears a Warning shirt during the credits scene)

- “Another Brick in the Wall (Part II)” by Pink Floyd (lyrics referenced on video/DVD release cover)

- “Cum on Feel the Noize” by Quiet Riot (covering Slade) (lyrics referenced on video/DVD release cover)

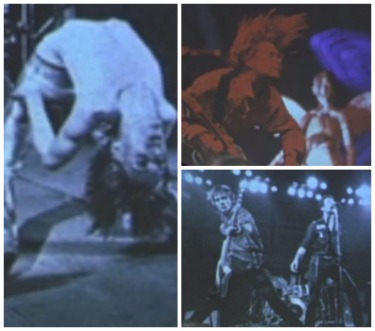

Video:

- Pete Townshend (The Who – guitarist)

- Jimi Hendrix (The Jimi Hendrix Experience/Solo – vocalist/guitarist)

- Angus Young (AC/DC – lead guitarist)

- Keith Moon (The Who – drummer)

Slideshow:

- Iggy Pop (The Stooges/Solo – vocalist)

- Ramones

- The Clash

- Kurt Cobain (Nirvana – vocalist/guitarist)

Riffs Played by Students:

- “Iron Man” by Black Sabbath (played by Zack on guitar)

- “Smoke on the Water” by Deep Purple (played by Zack on guitar)

- “Highway to Hell” by AC/DC (played by Zack on guitar)

- “Tough Me” by The Doors (played by Lawrence on keyboard)

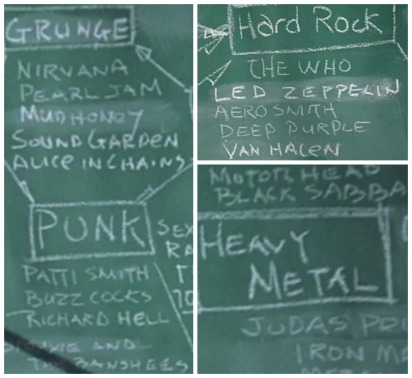

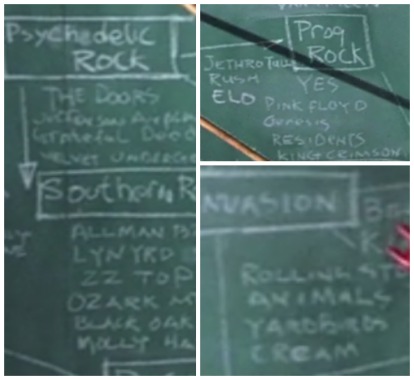

Blackboard:

- The British Invasion

- Hard Rock

- Heavy Metal

- Punk

- Grunge

- Soul

- Prog Rock

- Glitter/Glam Rock

- Funk

- Folk/Folk Rock

- New Wave

- Psychedelic Rock

- Pop Rock

- Southern Rock

- Disco

- Doo Wop

Soundtrack (songs from well-known artists, not songs only in the movie):

- “Substitute” by The Who

- “Sunshine of Your Love” by Cream

- “Immigrant Song” by Led Zeppelin (this track is surprising since Led Zeppelin is famous for never letting any of their songs appear in film or on television)

- “Set You Free” by The Black Keys

- “Edge of Seventeen” by Stevie Nicks

- “My Brain Is Hanging Upside Down (Bonzo Goes to Bitburg)” by Ramones

- “Growing on Me” by The Darkness

- “Ballrooms of Mars” by T. Rex

- “It’s a Long Way to the Top (If You Wanna Rock ‘n’ Roll) by AC/DC – (played by students at the end of the movie as the credits start)

Featured Songs Not on Soundtrack (songs from well-known artists, not songs only in the movie):

- “Back in Black” by AC/DC – (played when Dewey is assigning band members their positions)

- “Roadrunner” by The Modern Lovers

- “Stay Free” by The Clash

- “Ride into the Sun” by The Velvet Underground

- “The Wait” by Metallica (covering Killing Joke)

- “Do You Remember Rock ‘n’ Roll Radio?” by KISS (covering Ramones)

- “Moonage Daydream” by David Bowie

- “TV Eye” by The Stooges