The Lead-up

Full disclosure: I am a music startup founder.

Right now my earbuds are in, and my music is turned up so loud I can feel my spine shaking. Not because I’m angry or sad, but because I’m determined. I’m determined to put to rest the jaded notions that surround music startups, even if it takes me more than one post to do it.

I read an article on Medium today that postulated that part of the problem with music-tech startups is the passion which those music-tech founders have for their products or services. The piece concluded with this sentence: “Passion is great, but in the end, it often fades.” False.

The article, though written I’m sure with the best of intentions at shining a light on the challenges of music startups in the tech arena, is fraught with generalizations and assumptions, none of which are good to have for an objective point of view. The piece referenced a talk from Google User Experience Researcher Tomer Sharon, using it to bolster the premise that “music startups go at it about all wrong” (of course I’m taking some creative license here, but that seems to me to be the basic paraphrase of the piece).

In his talk which the piece points to, are six main points about executing the wrong plan, and how this dynamic seems to plague numerous founders. By the author’s own admission, the talk wasn’t music startup-focused, and the resulting analysis is just a serious of personal views. The application of these points to the large deadpool of failed music startups is understandable. After all it makes sense to look at a slew of failed projects and calculate the correlation and causation of their respective deaths. However, the piece takes too much latitude in my opinion, and shines a shadow on all future music startups for the sake of bolstering a (misleading) argument in the present.

The (Asserted) Problems and the Responses

Here are my responses to the six points in the talk, and subsequently in the article (the asserted points are paraphrased for the sake of simplicity:

Asserted Problem #1. Founders assume that their personal struggles are mirrored by a larger struggle that the world needs a remedy for (which the author admitted is something that does happen). Further, most people don’t care as much about music; most everyone besides you and your music friends is essentially a casual listener, and thus an insignificant statistic and/or demographic.

Response #1. In many areas, and in music as well, there are problems that avid fans/users identify that other, “more casual users/listeners,” might not identify until they can see an improvement (the proverbial before and after picture). Not every identification of a problem can or needs to come from a “casual” user. Sometimes it takes a trained and experienced eye to understand and be able to identify something as broken and to be able to innovate a way to fix it.

This has nothing to do with the passion that music startup founders have for music. It has to do with their ability to dissect an industry that they have come to know better than most, and be able to see room for innovation within it. The generalized statement that “most people don’t care as much about music as you do” is misleadingly false.

It first assumes that one (the founder) cares too much about music, or is in same way too in love with music so as not to be able to strategize accordingly. Secondly, it presumes to know what the music founder has in mind for an innovation, and already moves to the assumption that such an innovation will fail. And lastly, it presumes to generalize peoples’ unique affections for music without citing any real statistical proof.

People do care about music—in fact they care a lot. That’s the reason that Napster was such a snafu in 2000, and the reason that the music space will be the next crowded arena as numerous companies try to cut a niche in the space. People do care, though with each person at a varying degree, how can one possibly know that “most people don’t care as much as you do[?]”

Asserted Problem #2. Startup founders seek validation from friends and family, who tend to be biased.

Response #2. This is a problem that all startups face, not just music startups. The piece’s assertion that founders of a music startup essentially only congregate with similarly “music obsessed” individuals presumes to know the particular group dynamics of every music startup founder.

I am a music startup founder, but my social circles are filled with people who populate the music, tech, theater, science, medical, and legal fields. Therefore, to reduce my social circles down to individuals who “think like I do” is fairly pandering and presumptuous.

Asserted Problem #3. Listening to users rather than observing their behavior can lead to disaster, as it can lead to building something people say they want, as opposed to something they will actually use.

Response #3. Much like point #2, this is a conundrum that plagues all startups, not simply music-related ones. Therefore, it should be relegated to the list of startup mistakes to avoid, not used as a reason to forego building a music startup.

The author’s use of the company Jukely as a buttress for the argument actually brings into question the author’s own view of the music industry. The analysis is filled with wild generalizations like “[t]he live music audience [is mostly] made up of people in their twenties” and that “many people [can’t stay out late and see music because] they have a career and kids to think about.”

The former is false because it’s a gross generalization (and assumption, for that matter), of the age-range of all music-goers everywhere, failing to take into account different music scenes, tastes, geographical dynamics, or any number of other factors. The latter is negated (and thereby false) because it presumes to know the intra-familial and career dynamics, realities, and responsibilities of all music-goers everywhere. As a result, the whole analysis can’t be put forward in any sort of objective way, and must therefore be taken as a matter of opinion, not a matter of fact.

Asserted Problem #4. Most music startups don’t test their riskiest assumptions.

Response #4. This entire point negates itself because it purports to know every assumption that every music startup has, and every failure that came as result of ignoring those assumptions. Again, gross over-generalization is the culprit here.

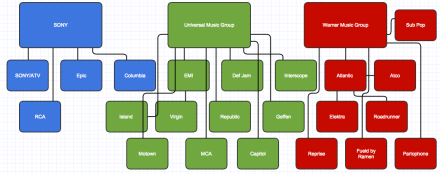

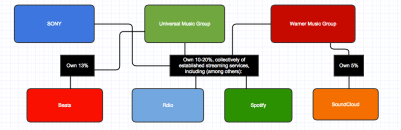

In the midst of arguing point #4, the author makes a bold statement that I can personally bear witness to as wholly false. The author writes: “The other risk startups take when entering the music space is that they simply don’t know anything about the music business.” I am a music startup founder, and I have spent nearly a decade in the music industry.

Though the author does make a good point—that the “launch first, ask questions later” approach isn’t suited well to the music industry—the point is negated by the assumption that all music startup founders are simply overzealous music fans with no understanding of the inner workings of the music business. I for one take offense to that.

I was in a band in high school, and after graduating, took a gap year before college, during which I was a music journalist. I continued my journalism well into my college career, even as I simultaneously ran a radio show and conversed with artists daily. In fact, I had press access at Warped Tour in 2012 precisely because of the connections I’d made and things I’d learned during my tenure as a journalist and DJ. All of these experiences and understanding are what I draw on every day to help formulate the best decisions for my music startup.

Me on my show, Underground Takeover

Me with: Those Mockingbirds (top left), Bloody Diamonds (top right), The Steppin Stones (bottom left), and Sunshine & Bullets (bottom right)

Me at Warped Tour 2012, with: June Divided (left), The Nearly Deads (middle), and Mighty Mongo (right)

Asserted Problem #5. Music startup founders become obsessed with can I build it, and lose sight of should I build it.

Response #5. Again, this is a problem that all startups must contend with. It seems that the author takes the most general points of avoidance made to most and/or all startups and sets them up as tools to bolster an argument that takes aim at music startups specifically. But in reality, if these are simply more general avoidances (seeing a pattern here?), then they have no place in this argument anyway, and are thus negated by their own generalization.

Asserted Problem/Response #6. The author actually doesn’t actually make a point #6. I assume it was meant to be taken or gleaned from the concluding paragraphs, but all that is left at the end of the piece is more generalizing. Statements like “[t]he music tech business is a graveyard littered with startups that seem cool at the time, [but no one wants or needs]” and “[the music founders] all went to SXSW, and lit some money, and crashed and burned a few years later” are more presumptuous than perhaps anything else in the piece.

The former of the statements asserts that no music founder could ever possibly create a music app or service people want/need, and the latter elevates SXSW to the pinnacle of godhood in the realm of music festivals. Yet if the author was familiar with the trends and grumblings that go on below the surface, then it would be understood that SXSW has in fact become sour to many independent music fans in recent years, as it leans further towards a mainstream agenda.

The last paragraph in particular is annoyingly pandering; its tone and diction betray a bitter and jaded writer using generalizations to bolster arguments of arrogance and assumptions.

The Last, False Sentence

Which brings us back to the last sentence yet again: “Passion is great, but in the end, it often fades.” Clearly the author is surrounded by other jaded personalities who forgot (or perhaps never knew) why most people get into the music business in the first place. It’s not about being the next Led Zeppelin or being rich and famous (though it’s fun to entertain fantasies); it’s because our passion is visceral—a part of us that we can’t turn off and on at will. It just exists as a nagging need, like the need to breathe when we wake up in the morning.

Passion can transform or ebb, but it rarely fades in the way that the author asserts it does. In the end, many of us in the music industry chose this business not because we wanted to solve some major problem (not at first); we chose it because it speaks to us in a way few other things do. That passion doesn’t fade. If anything, it gets stronger with every subsequent experience.