For those who may not know, we in the music industry are quite fond of lists. Best albums, best songs, best guitar players, etc.—we love to compile and compile. And we love to argue our points a thousand times over, and then a few more thousand times after that. It makes for good dialogue.

One of the more popular lists to compile now, though, has a bit more meaning behind it (in my opinion) than the writer simply touting his or her new favorite picks for the week. Lately, the list of annoying things that (local) bands do has been getting longer and longer, and they’re becoming more prevalent within the community. A good (though albeit too lengthy) example is the one that MetalSucks compiled back in 2008 which I’ve seen making its rounds again in the new year.

As I read through it again, however, it occurs to me that many of the points that are being made might very well apply to startups within the tech sphere as well (or any other industry for that matter). Malicious intentions not withstanding, numerous points jump out at me as translatable in an almost eery way. Thus I will take what I think are 10 of the most important points and translate them from the independent (local) music arena to that of the startup tech world. Let’s begin:

1. Bands who feel a need to bang on their drums and guitars in an annoying display of a lack of talent before the doors to the club have even opened = Startups that feel a need to tell you they will have the next big thing before they have written a line of code or made any effort to set up a structural base for a company. You’re not fooling anyone, and just come off as delusional and annoying until you have an actual product to play/build/sell. (The term “stealth mode” comes to mind).

2. Bands who have more roadies than actual band members = Startups that have more employees/cofounders than are actually needed to get the job done and run a company efficiently. You’re only hurting yourself in the end and people actually look at those extra cooks in the kitchen as a detriment too early on.

3. Bands who arrive at the club and state that they’ve talked to “someone” about a paying gig, but when asked who, can’t remember the person, all the while insisting that it was “just someone who worked at the club” = Startups who try to “network” by insisting they have a mutual contact and that the person has totally introduced you once before. Again, you’re not fooling anyone, and in fact are coming off as scheming and dishonest. Take the time to build the relationships you want to cultivate rather than trying to take the shortcut to your end goal.

4. Bands whose draw is so bad that even their guests don’t show up = Startups who have absolutely no feedback at all because not even their friends want to use and try out their product. If you can’t at least sell your music or product to your friends, you have a major problem.

5. Bands who have no guests because they have no friends = Startups who have no users or support because they too have no friends. This one is arguably an extension of #4. Takeaway: have a product that’s at least good enough for your friends to want to use it. (Double takeaway: don’t be a tool; have friends who want to champion you).

6. Bands who show up wearing “All Access” laminates at a club where “all access” means just about nothing since it’s just a stage and soundboard area = Startups who wear what they think they’re supposed to (maybe hoodies and quirky shoes) and act they way they think they’re supposed to (take this to mean whatever you will) in order to be “real” founders. Posing isn’t just an insult in the punk vein of the music industry; poseurs are everywhere and they are most easily identified as the people who seem really deep until you start interacting with them. Then you realize that they sing the song and dance the dance, but that’s about it. You don’t want to have this reputation as a band, and you certainly don’t when you’re a startup looking to break out amongst the competition.

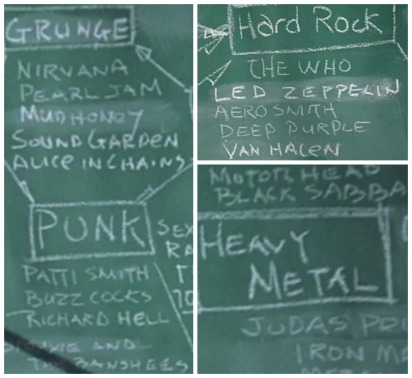

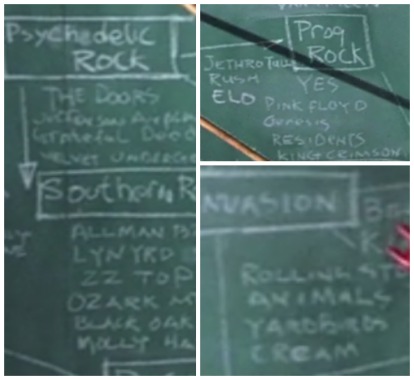

7. Bands who market themselves as “We’re ________, but with a mix of ________ and a hint of _________’s vocal/guitar sound” (Example: We’re just like Nirvana, but with some Green Day-style vocals and killer Van Halen guitar licks) = Startups who market themselves as “We’re _________, but for ________” (Example: We’re like Netflix/Uber/Facebook, but for candy/socks/refrigerators). No you’re not, and you’re cheapening both these companies and yourselves by suggesting so. If you have a similar business model, say that, but don’t speak in all analogies (especially since you want to distinguish yourself anyway).

8. Bands who can’t play longer than a 10-minute set = Startups who have no idea how to last longer than a few months (i.e. have not thought about any structure or organization of the company beyond the writing of the code). This tells investors, customers, and your peers that you’re not capable of sitting down with a pad and pen and planning out how to take your idea from: an idea => a working prototype => a viable, long-term business. This is a particularly essential thing to figure out before you take any financing (think of it as having more than 3 songs before you get up on that stage).

9. Bands who don’t even have enough respect for their fans and musical peers to stick around for the whole show after their set is finished = Startups who don’t even have enough respect for their peers to reciprocate feedback when they receive it. Seriously, this is both a stupid and jerk move. Firstly, it earns you a poor reputation as someone who won’t reciprocate the good will shown to you because one of your peers may end up “competing” with you sometime in the future. Secondly, it’s stupid because you lose out on anything you might have learned from the experience to make your own startup a better company.

10. Bands who grow supermassive egos and forget their fans and musical peers when they get a little taste of success = Startups who grow supermassive egos when they taste a little success and seem to forget their early supporters. Regarding bands/artists, yes this does happen (I’ve experienced it myself) and no, it doesn’t end well. Don’t forget the people who came out to your show before anyone knew you, or the other bands who took you on tour when you were nobody. Regarding startups, it may happen a little less often (in particular ways), but I can’t imagine it doesn’t happen at all (again, I’ve experienced it myself). Don’t forget your early supporters and believers, and certainly don’t ever forget your core customer-base. When the smoke clears, they’re most likely the only people who will stand by you (unless you’re very lucky).

These are just a few points that occurred to me to have crossover appeal and application. Certainly more exist, though I think these are the some of the most obvious. In many ways being in a startup is like being in a new local band (who would’ve thought?)—we should all strive to avoid these pitfalls. Otherwise, we’re just that crappy local band that everyone wishes would just finish their set and get off the stage.